Looking for Uncle Tom’s Cabin

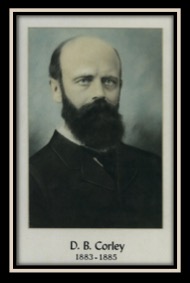

I live in Natchitoches, Louisiana, in the parish of the same name; in Louisiana, we have parishes and not counties. After my landlord and neighbor gave me a copy of a little travelogue published in 1892 titled A Visit to Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Daniel B. Corley, a judge and former mayor of Abilene, Texas, I went looking for Uncle Tom’s cabin. In the book, Corley described his mission to find the “real” Uncle Tom’s cabin and have it shipped to Chicago’s World’s Columbian Exposition, an international affair celebrating the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s arrival to America.

It is worth remembering what a literary phenomenon Harriet Beecher Stowe’s anti-slavery melodrama was. Uncle Tom’s Cabin: or Life Among the Lowly first appeared in print as a serial in the anti-slavery weekly The National Era, beginning June 5, 1851. The book sold 10,000 copies in its first week and 300,000 in its first year in the United States, becoming the 19th Century’s biggest selling work of fiction.[i] Abraham Lincoln is said to have remarked to Stowe when they met in 1862, “So you’re the little woman who wrote the book that made this great war.”[ii] In Corley’s day, the book and its impact were still felt.

Uncle’s Tom’s cabin never existed, but that did not deter Corley from traveling 430-plus miles east from Texas to Louisiana to find it and to construct a tale that might convince others he’d found something that never existed. What Corley found is a Louisiana landscape imbued – due to slavery – with a haunted and tragic past. If a plantation ever existed like the one Tom’s evil killer Simon Legree would own, it would be here.

“Late in the month of August, 1892,” Corley wrote, “I decided to make a visit to the old plantation in Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana, where I knew the original ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’ was still standing, just as it stood the day that the old slave died the tragic death accorded him.”[iii] In Natchitoches, a town claiming to be the “oldest permanent settlement in the Louisiana Purchase territory,” he found locals ready to tell him that Harriet Beecher Stowe likely based her Legree character on a slave owner named Robert McAlpin who owned a plantation in the “lower portion of the parish,” about 25 miles south of town. As Corley learned, McAlpin “was notoriously cruel to his slaves. That at times they would despair and kill themselves.”[iv] A courthouse clerk surmised that Stowe’s creation became a roman à clef to keep McAlpin from suing her for “slander or defamation of character.”[v]

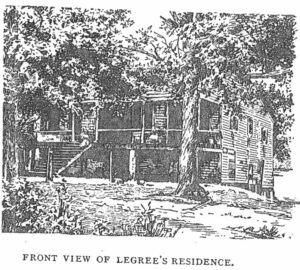

Corley created plausibility so that any reader of Uncle Tom’s Cabin and his travelogue would find favorable comparisons between McAlpin’s plantation, now owned by one L. Chopin, and Legree’s fictional one. In the novel, as Tom arrived at that plantation, Stowe wrote his wagon rolled along a “weedy gravel walk, under a noble avenue of China trees, whose graceful forms and ever-springing foliage seemed to be the only things there that neglect could not daunt or alter–like noble spirits, so deeply rooted in goodness as to flourish and grow stronger amid discouragement and decay.”[vi] As Corley arrived at the McAlpin Plantation, he found similar trees prompting this claim: “These trees have grown until they now have large trunks ranging in size from two to three feet in diameter…[and] if properly looked after and protected from fire their ‘graceful foliage’ will enable the historians to unmistakably locate the tragically historic spot in the year 2000.”[vii]

As Corley walked up to a slave cabin, his literary pretense continued:

As we approached it I could not help feeling a profound and deep reverence for both the place and the “cabin.” In fact, it seemed to me as if I were treading upon sacred ground, and when halting in front of the house, I must admit, that the feeling that crept over was akin to that feeling which would have come over me, had I been approaching the tomb of some patriarch of old. It was the last earthly home and place of “Tom,” the chosen instrument of Almighty God for showing to this world the evil of one man enslaving another.[viii]

As Corley entered the shack, he staked a further claim:

We entered – all was still; the black, smoked logs with here and there a two-inch auger hole bored into their inside face into which pins or pegs were once used as supports for shelves, were plainly visible. From these it could be seen that a number of these shelves once ranged around the room. I looked and wondered which one of these “Tom” kept his Bible on. But which one it was of this number there is no mistake. [ix]

Yet, any reader of Uncle Tom knows that Stowe described a far more depressing situation for Tom who looked onto “a little sort of street of rude shanties, in a row, in a part of the plantation, far off from the house. They had a forlorn, brutal, forsaken air.” These “were mere rude shells, destitute of any species of furniture, except a heap of straw, foul with dirt, spread confusedly over the floor, which was merely the bare ground, trodden hard by the tramping of innumerable feet.”[x] No shelves for Bibles here.

Still, Corley informed his readers that he was “thoroughly satisfied as to the identity of the plantation as that of the Legree of Mrs. Stowe’s narrative of ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin,’” and “closed a trade with Mr. Chopin by which he gave me a lease on the cabin for the purposes of exhibiting it at the World’s Fair at Chicago, and such other places as I might deem fit to exhibit it afterward.”[xi] Off to Chicago the cabin went where it was reassembled at “the Libby War Museum on Wabash avenue.”

I doubt that Corley was a huckster, but he wanted to make a buck after his hard work to find Uncle Tom’s cabin. He reminded travelogue readers venturing to the Exposition: “In visiting this world-renowned house, and when there, by no means fail to purchase a souvenir for the dear ones at home. We have a great variety of walking sticks, beautiful rattan, that grew upon the plantation, and cotton balls from the plantation, done up in nice boxes with a clear-cut picture of the cabin on the box.”[xii]

In my quest to find Uncle Tom’s cabin, I tried to retrace Corley’s route and drove out of town, down Louisiana Highway 1 toward the town of Chopin. A single-line railroad track parallels the highway, and the land is mostly flat, wet, and green with abandoned houses and businesses and signs and sheds dotting and dissolving into the green landscape. After passing the Little Eva Pecan Company and its “Harvest of Delights from our Bountiful Groves,” Chopin is near but not really. It is only an intersection not far from the entrance to I-49. I looked for that grove of Corley’s China trees that will “enable the historians to unmistakably locate the tragically historic spot in the year 2000.”[xiii] But like Chopin, they no longer exist–and neither did Uncle Tom’s cabin.

NOTE: Stowe had many sources for her novel, and the former slave Josiah Henson, who later escaped to Canada, is often considered the model for Uncle Tom. Henson wrote in his autobiography about his contribution to Stowe’s book:

I have been called ‘Uncle Tom,’ and I feel proud of the title. If my humble words in any way inspired that gifted lady to write such a plaintive story that the whole community has been touched with pity for the sufferings of the poor slave, I have not lived in vain; for I believe that her book was the beginning of the glorious end. It was a wedge that finally rent asunder that gigantic fabric with a fearful crash.[xiv]

If one really wants to see Uncle Tom’s cabin, that person must head to southwest to Ontario, Canada, where the Ontario Heritage Trust is keeping watch over Josiah Henson’s cabin.

Brian Gabrial’s research on the 19th-century press has had a focus on slavery in the antebellum American press, 19th-century press coverage of Native Americans, and the Canadian press and nationalism before, during and after confederation. He is the current Wise Professor of Journalism and Northwestern State University of Louisiana and a professor emeritus at Concordia University in Montréal.

[i] harrietbeecherstowecenter.org/harriet-beecher-stowe/uncle-toms-cabin/ (retrieved April 16, 2022).

[ii] The veracity of this quote is not certain. See stowehousecincy.org/blog/what-did-lincoln-say-to-mrs-stowe, (retrieved May 7, 2022).

[iii] D. B. Corley, A Visit to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, (Chicago: Laird and Lee, 1892), p. 3.

[iv] Ibid., 13.

[v] Ibid., 5.

[vi] Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, (Ann Arbor, MI: Borders Classics, Ann Arbor, 2006), 356.

[vii] Corley, 26-27.

[viii] Corley, 17.

[ix] Ibid., 20.

[x] Stowe, 358.

[xi] Corley, 36.

[xii] Ibid., 40.

[xiii] Corley, 26-27.

[xiv] Josiah Henson, Uncle Tom’s Story of his Life: An Autobiography of the Reverend Josiah Henson, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library a DocSouth Edition, 2011), p. 120, (retrieved April 23, 2022).