Against Split Personality Pedagogy

Teaching literary journalism reporting techniques across the journalism curriculum

*Editor’s note: This article is from our archives. It originally appeared in Literary Journalism vol. 13, no. 2 (2019).

If you’re reading this article, you’re likely already engaged in the teaching and study of literary journalism. But you probably also teach classes other than literary journalism, which can lead to a phenomenon I call “split personality pedagogy.”

Split personality pedagogy goes something like this: In the morning you teach an introductory reporting class, your focus on urging students to get the details of a press conference right and developing a clear, concise and pithy prose style. In the afternoon, your upper level literary/narrative/magazine journalism students feast on the richer fare of Didion, Hunter S., Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah, and John McPhee, inspiring them to explore new ways of approaching their own writing and reporting.

There are good reasons to make what at first feels like a clean divide between a.m. and p.m. It’s difficult to teach the fundamentals of writing and reporting. You have to get students to tackle the verbosity that comes from years of misguided notions about good writing. An elective in literary journalism, typically later in a student’s academic career, can come across as the reward for a job well done, for understanding the rules well enough to consider what it means to break them.

Early in my journalism teaching career I went with the split personality approach. It felt safer, the variables under control. But after a while it began to feel intellectually dishonest. I wasn’t reporting or writing in the inverted pyramid, third person omniscient straightjacket. Most of what I read wasn’t written that way, either. Certainly, the best journalism I was reading was not written that way.

We are better off from the start teaching students that journalism is a constellation of genres and styles, with literary journalism among the brightest stars. Literary journalism is foundational to what journalism is. Teaching it throughout the curriculum helps students see journalism as intellectual inquiry and an endeavor that has the capacity to humanize news and information.

The following are what I hope will a useful set of “read” and “do” tips for infusing an undergraduate journalism curriculum from the introductory to advanced level with the study and practice of literary journalism. The tips are based on the journalism major at SUNY New Paltz, where I teach.

Introductory level: Read

Assign a current work of longform journalism that uses literary journalism techniques to show how character and story-driven reporting facilitates credibility and reader investment. I like to pick topics that are already on our students’ minds and in the public conversation. Examples: “When Children Say They’re Trans” by Jesse Singal in The Atlantic; “The Challenge of Going Off Psychiatric Drugs” by Rachel Aviv in The New Yorker.

Introductory level: Do

Have students do a 45-minute observation in a public space on campus in which they write down only visible, tactile, hearable and smell-able details, without opinion, judgment or feelings. They then use their notes to write a short sketch of the setting that shows its unique character (H/T Dr. Rachel Somerstein).

Intermediate Level: Read

One goal in intermediate level feature writing and magazine writing courses is to get students to write about their subjects “in action” in a scene and what they have to do as reporters to make that happen. I love to teach Rolling Stone profiles because the strategizing is so overt. “A Trans Punk Rocker’s Fight to Rebuild Her life,” Alex Morris’s profile of Laura Jane Grace, is framed by Grace getting a tattoo, an obvious set up for getting action into a story, useful for students baffled by the concept. A subtler choice is “Portrait of an Artist as a Postman,” Jason Sheeler’s Texas Monthly profile of Kermit Oliver, an African-American postal carrier who makes paintings reproduced as Hermes scarves. Sheeler acutely observes Oliver’s hermitic and tragic existence, to powerful effect.

Intermediate Level: Do

Assign a profile that must include a scene of the subject in action. This fundamental assignment is probably familiar to many of you. I’ve been amazed in my 15 years of teaching journalism how challenging and unintuitive this “scene requirement” has become for students—and thus how important! Students find it challenging to arrange to be in the presence of someone, which requires them to explain to their subjects why they need to “hang out” for a while and bear witness to some aspect of their lives. Some helpful tactics:

- Give students a theme for the profile. Recent ones I’ve used: change makers; people living on less than a living wage.

- Assign video supplements, which helps students see the power and necessity of spending time with their sources.

- Emphasize the power of feature/magazine/narrative writing, in process and product, as an antidote to the disembodiedness of digital life.

Advanced Level: Read

In our Capstone Seminar in Multimedia Reporting, I assign a wealth of multimedia longform reporting in the legacy of The New York Times’ “Snow Fall,” which rely heavily on literary journalism and narrative techniques. A couple of favorites: - “The Shirt on Your Back,” a richly produced, immersive feature in The Guardian on the global clothing industry.

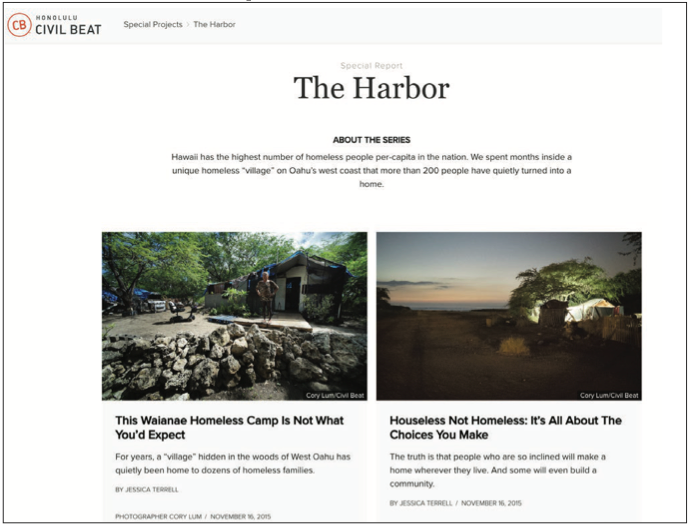

- “The Harbor,” The Honolulu Civil Beat’s series on a homeless encampment on Oahu. The The Honolulu Civil Beat’s series is not as technically sophisticated or expensive as “The Shirt” or “Snowfall,” which provides a more doable model for students.

Advanced Level: Do

Students write a longform article (3,000- 5,000 words) using Jack Hart’s “3+2 structure of explanatory reporting”: narrative + context + narrative + context + narrative. Students can’t sustain this structure without powerful storytelling, strong central characters, and keen observation skills. In my course, students also produce multimedia supplements and data visualizations.

Lisa A. Phillips is an Associate Professor and chair of the Department of Digital Media and Journalism at the State University of New York at New Paltz. She is the author of Unrequited: Women and Romantic Obsession (HarperCollins) and Public Radio: Behind the Voices (Perseus). A former public radio reporter, she focuses her journalism and nonfiction writing on issues related to love, heartbreak, and mental health, with bylines in The New York Times, The Washington Post, Psychology Today, Cosmopolitan, Longreads, and Salon, among other outlets. Her scholarly research interests include first person journalism and media ethics. phillipl@newpaltz.edu