Finding a New Normal

Technology and grit are the keys to pandemic-era narrative nonfiction

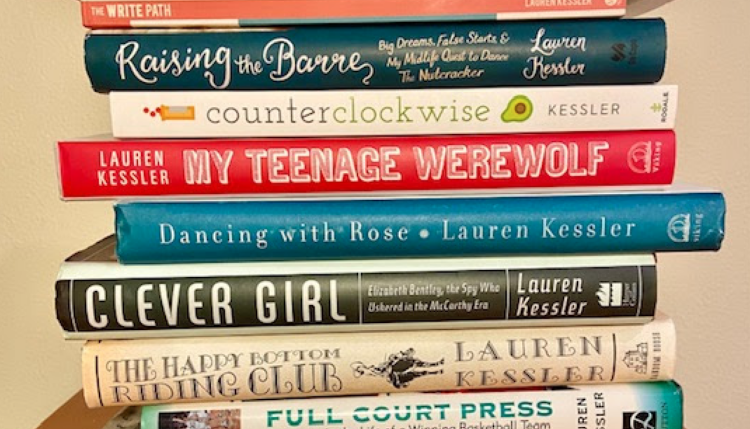

I am a literary journalist, a narrative nonfiction writer. But I am also, for want of a better term, a “cultural anthropologist without portfolio.” (The “portfolio” I am without is a university degree in that subject.) What I do, what I have done for my last six books, is anthropological: I immerse myself in the subculture I want to explore and write from the inside out. It began with Dancing with Rose when I took a job as a bottom-of-the-rung caregiver at a residential Alzheimer’s facility to try to understand the life lived by those with the disease. For my next book, My Teenage Werewolf, an exploration of teen girl culture and the oh-so-fraught mother-daughter relationship, I embedded myself in middle school. For eighteen months. (I suggest you never do this.) For Counterclockwise, I used myself as a guinea pig to investigate the real and evolving science of aging and the Internet-fueled commercial world of “anti-aging” in an attempt to separate hope from hype. I joined a ballet company for Raising the Barre. I volunteered as a writing teacher in a maximum security prison for Grip of Time. With the research for each of these books, being there was the key, being present was my m.o. Nora Ephron famously wrote about this kind of reporting, dubbing herself “a wallflower at the orgy.”

I started the wallflower-style research for my new book, Free: Two Years, Six Lives, and the Long Journey Home, six months before the pandemic. The work was to be an exploration of the road traveled by hundreds of thousands of men and women (600,000 a year, to be exact) from caged to free, a narrative-fueled chronicle of the challenges faced by people released from decades behind bars into a world they did not understand and that, too often, did not understand—or welcome– them.

I started the wallflower-style research for my new book, Free: Two Years, Six Lives, and the Long Journey Home, six months before the pandemic. The work was to be an exploration of the road traveled by hundreds of thousands of men and women (600,000 a year, to be exact) from caged to free, a narrative-fueled chronicle of the challenges faced by people released from decades behind bars into a world they did not understand and that, too often, did not understand—or welcome– them.

I knew something about the culture of prisons from my previous embedded work in the penitentiary. I knew what one had to become to survive that experience, and I knew (and the research told me) that those same strategies were ill-suited to life in the free world. The transition would be extraordinarily challenging. I felt that in-the-moment stories of those released could reveal both the severe shortcomings of the prison system and the remarkable resilience of those who had spent so much time within it. I wanted to explore, by watching and listening, by learning: How did people go about reclaiming and remaking their lives?

I spent considerable time finding these folks, choosing six men and women, diverse in every way other than the fact that all had spent decades behind bars. I spent even more time building the kind of trust that is essential to this work. In life—and perhaps more so in incarcerated life—trust is hard to earn and easy to lose. I was lucky that I could use my previous book, Grip of Time, as a calling-card. I was even more fortunate to have the active support of the men I had mentored in prison. I was vouched for, and that made all the difference. In asking to be an observer to their re-entry journey, I was asking these six to let me see their struggles, their insecurities, their confusions, their missteps, not just their successes.

What I found, as I watched them leave the gate or sat with them later listening to them recount that moment, were folks who were simultaneously joyful and overwhelmed at the prospect of freedom. They were anxious, confused, sometimes terrified, alternately numb and giddy. They wanted to do everything all at once, but often could not figure out how to do the simplest of things. I was learning so much.

And then, this virus no one had ever heard of came roaring into our lives, came barreling into my life as an immersion journalist, and up-ended my wallflower days. I could not meet up with these folks. We could not hang out in coffeehouses. I could not visit them in their apartments or watch them at work. Sit with their families. And so I threw myself into what I could do. I read sociological studies, government reports, legal documents, first-person accounts. I listened to podcasts. I combed the online world for news of organizations that were involved in re-entry. I exchanged emails with the men and women whose lives were now hidden from me. And then there was Zoom, so much better than Skype, and at least we could see one another. This felt second-rate to me, but occasionally I would be surprised. On a Zoom call with Arnoldo I witnessed an ordinary/extraordinary moment between him and his toddler, one that might not have happened had I been in the room.

Still, I so much wanted to be there. But as the quarantine months dragged on, and there seemed no end to this “new normal,” I forced myself to stop mourning for what I couldn’t do and start thinking of what I could do. My pandemic reporting methods would have to depend not on physical proximity but on technology. I was “there” the morning Isaac was released because Cheryl, who picked him up, Face-Timed with me for two hours. I was “there” via intense real-time texting and Marco Polo. When that wasn’t possible, I was “there” later through images and video caught by others or recorded by the men and women themselves. This sharing was an act of trust. And I may have learned more about them by what they recorded and shared than I would have had I been there.

The challenge of this work has forced me to grow and adapt, to navigate uncharted waters, which has helped me to better understand (and so deeply admire) the navigation skills of my characters. What I hope with this new book is that readers feel caught up in the moment, whether I was there or not.

Lauren Kessler is a narrative nonfiction writer who specializes in exploring invisible subcultures in our midst. She has written about everything from the gritty world of a maximum security prison to the grueling world of ballet to the surprisingly vibrant world of those with Alzheimer’s. She ran a writing group for lifers inside a maximum security penitentiary and volunteers as a mentor at a prison reentry services nonprofit. Founder and director of a graduate program in literary journalism at the University of Oregon, she currently teaches storytelling for social change at the University of Washington.

Lauren Kessler is a narrative nonfiction writer who specializes in exploring invisible subcultures in our midst. She has written about everything from the gritty world of a maximum security prison to the grueling world of ballet to the surprisingly vibrant world of those with Alzheimer’s. She ran a writing group for lifers inside a maximum security penitentiary and volunteers as a mentor at a prison reentry services nonprofit. Founder and director of a graduate program in literary journalism at the University of Oregon, she currently teaches storytelling for social change at the University of Washington.