Literary Journalism In Fin-De-Siècle Vienna

A cultural tradition of newspapers.

*Editor’s note: This article is from our archives. It originally appeared in Literary Journalism vol. 12, no. 2 (2018).

Newspapers may not be the first cultural output that springs to mind in connection with Vienna, a city best known for its artistic and intellectual accomplishments over the last century. Instead, one might think of Klimt’s lovers perhaps. Or Strauss’ waltz. Freud’s couch. Maybe even Wittgenstein’s rabbit.

But for the Viennese of the fin de siècle, it was hard to overestimate the newspaper’s importance. “Vienna without the newspaper. That is: Vienna without Vienna,” journalist and coffeehouse literatus Anton Kuh once quipped. “The city comes to life only when it sees itself in print.” [1]

This centrality was due in large part to the city’s devotion to the feuilleton, a departmentalization for arts and culture, which, in the years leading up to the First World War, placed the worlds of literature and press together in a remarkably close and at times uneasy embrace.

Originating in Paris in the early nineteenth century, the feuilleton featured short amusing reports and criticism on the lower half of the paper’s first page; a segment separated from the political section by a heavy black line. The Viennese press took up the practice in 1848, and over the next fifty years the feuilleton became its most beloved feature. A sacred site even, in the estimation of author Stefan Zweig, who, in his memoir The World of Yesterday, described the feuilleton as an “oracle” of knowledge and taste that readers consulted daily. [2]

Style had much to do with the enormous popularity of the feuilleton. The form encouraged playfulness with language and the free flow of thought. It was a natural medium for the impressionism that defined Vienna’s particular brand of literary modernism, and made room for the innovative forms of Kleinkunst—the gloss, sketch, textual montage, and aphorism—favored by young literary stars like Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Alfred Polgar, Felix Salten, and Zweig himself.

This association between the feuilleton and aspiring literary artists produced a literary journalism full of charm and grace. But it also attracted intense criticism, occasionally even from famed feuilletonists, like Polgar, who wrote:

The essence of the Viennese feuilleton: emptiness; a watery visage daintily framed with frizzed stylized curls. …About life the Viennese feuilletonist always has something graceful-novel-distinctive-ironic to say even when he has absolutely nothing to say about the tiny piece of life (book, person, event) that he has put under discussion…. His soft oiliness has gotten unpleasantly rancid. It stinks. [3]

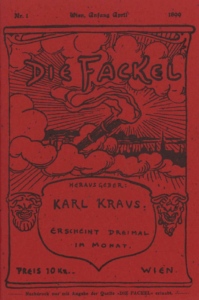

Early twentieth century commentators—in particular the crusading press critic Karl Kraus—argued that the tendency to privilege the author’s subjectivity led to trivialized content and cheapened language. It turned the intellect (Geist) into a “glazing” for modern commercialism and other forms of outside influence. [4] German scholar Paul Reitter phrased this another way, commenting that the language of “the heavily ornamented Viennese feuilleton acts upon the imagination of the readers in such a way that the virtual reality of journalistic reportage determines the external reality it should cover.” [5]

The First World War brought this problem into sharp relief. External reality was nowhere to be found in the wartime pages of Viennese feuilleton, which participated, even if sometimes reluctantly, in what historian Edward Timms described as “the conversion of poets to patriots.” [6]

After 1918, feuilletonism seemed compromised, or at least out of sync with rapidly shifting postwar literary and journalistic values. The press regrouped with a newfound emphasis on news and political coverage, and the interwar generation adopted a new cultural doctrine: Neue Sachlichkeit, or New Objectivity, which exerted itself with particular force in the arts.7 The “visionary poet” of the press was replaced by the “intellectual worker,” armed with the tools of “factual knowledge, documentary precision, [and] scientific rigor.” [8]

Vienna’s devotion to literary forms of journalism remained, even after the correction of what Egon Erwin Kisch called the “colossal overestimation” of the feuilletonist over the reporter.9 The city’s papers, for example, helped launch the careers of the some of the most celebrated literary journalists of the interwar period, including Kisch and Joseph Roth.

All of this came to an end with the Second World War, which devastated Vienna’s newspaper culture. Today, little remains beyond the famed cafes where these young writers gathered to write, read each other’s work, and enjoy the large spread of publications at one’s disposal for the price of a cup of coffee. For the journalism-loving visitor, any of these cafes is worth a stop. Prop a stick-skewered newspaper upon a marble tabletop and get a small feeling for the city as it was one hundred years ago, “a world,” as Karl Kraus observed “that live[d] between the morning and the evening edition.” [10]

Notes

[1] ”Wien ohne Zeitung,“ Prager Tageblatt, 20 January 1918, in Anton Kuh, Zeitgeist im Literatur-Café: Feuilletons, Essays, und Publizistik: neue Sammlung, ed. Ulrike Lehner, Vienna: Locker, 1985, 26-29.

[2] Stefan Zweig, Die Welt von Gestern (Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Verlag, 2001), 123.

[3] Alfred Polgar, “Feuilleton,“ in Kleine Schriften, vol. 4, ed. Marcel Reich-Ranicki and Ulrich Weinzierl (Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt, 1984), 200-205.

[4] Karl Kraus, “Heine und die Folgen,” in Grimassen: Ausgewählte Werke 1902-1914. ed. Dietrich Simon, Kurt Krolop and Roland Links, (Munich: Georg Müller Verlag, 1971), 293.

[5] Paul Reitter, The Anti-journalist: Karl Kraus and Jewish Self-Fashioning in Fin-de-siècle Europe (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008), 177.

[6] Edward Timms, Karl Kraus: Apocalyptic Satirist, Culture and Catastrophe in Habsburg Vienna (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986), 292.

[7] Kurt Paupié, Handbuch der österreichischen Pressegeschichte 1849-1959, Band 1:Wien (Vienna: Wilhelm Braumüller, 1960), 41.

[8] Jürgen Heizmann, Joseph Roth und die Ästhetik der Neuen Sachlichkeit (Heidelberg: Mattes Verlag, 1990), 39-39.

[9] Egon Erwin Kisch, “Wesen des Reporters,” in Gesammelte Werke in Einzelausgaben, vol.9, ed. Bodo Uhse and Gisela Kisch (Berlin: AufbauVerlag, 1976), 205.

[10] Karl Kraus, “Die Vertreibung aus der Paradiese,“ Die Fackel 1, nr. 1 (1899), 12.

Image Credits

Cover image: Reinhold Völkel, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Body images: Wiener Werkstätte, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons; Reproduction of the original cover of Die Fackel (public domain), via Wikimedia Commons.

Kate McQueen is lecturer at University of California Santa Cruz. She specializes in the history and practice of literary journalism, with a focus on narratives of crime and justice. For IALJS, Kate serves as book review editor of Literary Journalism Studies, and is on the editorial team of Literary Journalism, the IALJS newsletter. Outside of academia, Kate directs special projects for Prison Journalism Project.

Kate McQueen is lecturer at University of California Santa Cruz. She specializes in the history and practice of literary journalism, with a focus on narratives of crime and justice. For IALJS, Kate serves as book review editor of Literary Journalism Studies, and is on the editorial team of Literary Journalism, the IALJS newsletter. Outside of academia, Kate directs special projects for Prison Journalism Project.